I am not a Dead Head.

And though I learned my rock-and-blues electric-guitar chops in the 1960s, I was just never a fan of Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead.

But I am a Ray Robertson Head.

So if Ray wants to tell the story of Jerry Garcia and his psychedelic jam-band (framing his narrative around their fifty most memorable concerts), then okay, I’ll go along for the ride. Because whether he’s contemplating torpid Ontario suburbs or the pleasures of pot or the demise of independent bookstores or the frantic final days of Jack Kerouac, a Ray Robertson book is always a trip worth taking. His writing has never let me down, so, Dead Head or not, let’s have a closer look at All The Years Combine: The Grateful Dead in Fifty Shows (Biblioasis, 2023), Ray Robertson’s personal take on one of America’s most famous and/or infamous rock bands.

One theme running through much of Ray Robertson’s work is the age-old creative dilemma faced by those who are fully committed to pursuing their creative vision and maintaining their artistic integrity in a culture of consumer conformity and commercial compromise. Right from the start, in his debut novel Home Movies, Robertson gave us a fictional protagonist (country-and-western songwriter James Thompson) who refused to “compromise purity of execution for cross-over radio possibility.” A local reviewer praises James for playing country music “as it should be played - with honesty, energy, and emotion - and not just an anthem for ignorant rednecks,” while a supportive buddy encourages him “not to give in like everybody else in this goddamn town … Do the thing you were put on earth to do - play good honest music.”

Many of Robertson’s novels - like Home Movies (1997), Heroes (2000), Moody Food (2002), Gently Down the Stream (2005), What Happened Later (2007), and I Was There The Night He Died (2014) - follow protagonists who struggle with creative dilemmas, while his non-fiction Lives of the Poets (With Guitars) (2016) explores in depth the careers of Townes Van Zandt, Gene Clark, Ronnie Lane, Willie P. Bennett and others who learned the hard way that “principled devotion and sacred servitude” to their musical muses did not necessarily translate into commercial success in a world “where Englebert Humperdinck is a millionaire with hundreds of thousands of devoted listeners and you have to eat ketchup sandwiches.”

The Grateful Dead, says Robertson, likewise proclaimed from the very beginning their “indifference to the blessed twin sanctities of popular esteem and economic security … refusing to break a sweat for anything as ignoble as popularity or prosperity.” (They did, however, break a sweat for their music. Robertson describes how “the group’s idea of goofing off was practising eight hours a day,” and notes their “almost Zen-like concentration and commitment [and] long hours of practice, practice, and more practice.”)

Through much of their thirty year career the members of the band eschewed financial gain, preferring to nurture their own idiosyncratic muse. “In a world of stultifying - and increasing - homogeneity (artistic and otherwise), the Dead, at their best, resist predictability and conventionality. Thrive on it, in fact.” But, says Robertson, “there’s a price to be paid for doing what you want.” He describes, for example, the band’s 1976 decision to perform six shows in a small local theatre rather than one huge show in a 13,000-seat arena:

“No matter how young or zealous you are, it would take an extraordinary amount of energy and commitment to simply attend six Grateful Dead shows in seven nights; when you’re talking about performing those same shows - the price (physical, psychological, and creative) is incalculable.”

The story of the Dead, as told by Robertson, is a story of “calamitous financial affairs [and] pecuniary fiascos. … [Their] music-first aesthete was a lot easier to pull off when no one had kids and mortgages and expensive drug habits.” Robertson once said in an interview that for the Grateful Dead “it was a question of how much can you flirt with the mainstream without being consumed by it.”

Inevitably, however, and despite their “reluctant road to rock-star glory,” the band’s fanatical work-ethic (and equally fanatical fan-base) eventually brought them to the very topmost of the top-grossing touring bands in the world, grossing $55 million in a single weekend. “It’s rare,” says Robertson, “but commerce and art aren’t always enemies.” In this case, however, it was a Faustian bargain, for with commercial success the “Grateful Dead Incorporated” became a “keep-on-truckin’-on business entity dictating that they generate more and more income.” In his inimitably distinctive style, Robertson points out the “incongruity of a bunch of stoned, merrymaking beatniks partnering up with a suit-and-tie mega corporation. How did we end up as businessmen? When exactly did this become a job?” The iconoclastic band “who were once synonymous with the counterculture, had somehow become the mainstream.”

While the spring of 1990 included some exceptional performances (at their 3/29/90 Nassau concert with Branford Marsalis the Dead were “cookin’ again”), during their final years a Grateful Dead concert could be “about as inspiring as the concrete box where it was taking place.” The anti-establishment icons of the psychedelic ‘60s had become commercially dependable: “Dependable is good,” says Robertson, “when you’re buying snow tires or listening to a weather forecast; it’s not so good when your ostensible goal is to stir up awe and break open brainpans and pour iridescent illumination inside.” And even their ever-faithful Dead Heads were finding that “three or four minutes out of a couple of hours isn’t very satisfying musical math.”

From the band’s earliest days as Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions (a friend had to remind them to stand up when they played their first gig at a pizza parlour “in front of a handful of pizza-pie-munching strangers”) to the “jazz-rock conjurers at their creative peak” to the “lumbering MIDI-manacled monolith” of their stadium-filling world tours, the Grateful Dead - like so many of Robertson’s protagonists - were forever bemused by this creative dilemma of staying true to their vision in a world expecting conformity and compromise.

While master story-teller Robertson conjures up an engrossing comic-tragic narrative arc, it is the way he tells the story that sets this book apart from the plethora of other Grateful Dead books. Robertson once proposed his own criteria for good writing - in Mental Hygiene: Essays on Writers and Writing (2003) - applauding any author who “delivers a well-crafted, engaging tale [and] attempts to infuse the language with verve and swagger and supply as much wit and wisdom as the form will allow.” In the same vein, Robertson once called author Thomas McGuane “the reason I wanted to be a novelist,” praising McGuane’s “masterful mix of profundity, hilarity and linguistic dexterity [and] lexical mastery.” And in the course of publishing fifteen books (fiction, non-fiction, and poetry) Robertson has consistently exemplified his own criteria. “Word drunk” is a common publisher’s blurb on his book covers, and “linguistic fireworks” have always been a distinctive component in the DNA of Robertson’s writing.

In All The Years Combine, Robertson does indeed “stretch and sever and reconfigure language in sometimes startlingly fresh ways.” Here for example is his lexical catalogue of the “characteristic genre hopping” of a band determined “to go boldly where no rock band had gone before.” In full linguistic flight he describes their music variously as: “twisted Americana … shit-kicking cosmic-country … garage-rock be-bop … nouveau-voodoo … psychedelic neo-vaudeville … pumped-up polka … post-apocalyptic dirges… sci-fi skronk … and boogie-till-you-puke blues-rock.”

Ignoring Hemingway’s advice, Robertson literally revels in adjectival adventures, such as when describing the Dead’s various tones and styles: “dark dirges … silky slices of post-apocalyptic sorrow … evanescent, sad, beautiful … bubbling cosmic soup … achingly elegiac … smooth as a stick of warm cannabutter.” A Grateful Dead concert is “transcendent, aural ecstasy … wave after wave of jubilant Garcia guitar notes fluttering, floating, filling the nose-bleed section … played and sung with palpable glee and grit … energetic rockers and beauteous ballads and everything in between … from teeth-rattling, celestial cacophony to silky, stargazing aplomb … an acid-kissed psychedelic postcard from the past.” The Grateful Dead are “the cosmic clown jesters of contemporary music … blasting out sunshine-daydream sunbeams from start to finish.” Whew! Let me catch my breath. Dead-Shmed: I’m here for the pure joy of Robertson’s linguistic fireworks.

… and for his humour!

Tongue in cheek satire and laugh-out-loud humour have always been a key aspect of Robertson’s distinctive voice. A random sampling of witty aphorisms from other works sets the tone:

Trying to be happy is like trying to be tall.

Baseball wasn’t hockey, but still, it was somewhere to rest your brain.

There are worse habits than politeness.

In All The Years Combine it’s game-on for more aphorisms and that distinctive Robertson wit:

If you’re going to make a Grateful Dead omelette, you’re going to have to break a few songs.

If you hang around the numinous long enough, don’t be surprised to find magic in your muesli.

When the band descends into “clodhopping” rhythms, “it’s time for a bathroom break or time to hit the fast-forward button.” If their closing medley doesn’t “compel you to your feet, it’s time to take up tiddlywinks,” and on a bad night, says Robertson, the Dead sound like “Chuck Berry with a limp.” Time and again we witness the band playing in an “archetypal late-twentieth-century, all-purpose, suburban concrete shitbox” while at other times we watch their roadies “squeezing six hundred speakers into century-old theatres built at a time when an electrical socket was a big deal.” But, adds Robertson, never missing a comical insight, “at least they had somewhere good to hide their drugs.”

… and for his philosophizing!

Robertson, who graduated from the University of Toronto as a Philosophy major, has often woven metaphysical themes into his writing. At least two previous fictional protagonists (in Heroes and Gently Down the Stream) procrastinate over their doctoral dissertations in philosophy, while the narrator of Estates Large and Small (2022) takes a deep dive through 2500 years of Western philosophy. Similarly, philosophical explorations underpin his non-fictional works like Why Not: Fifteen Reasons to Live (2011), How To Die: A Book About Being Alive (2020), and The Old Man in the Mirror Isn’t Me: Last Call Haiku (2020). So it’s not surprising that All The Years Combine opens with a metaphysical metaphor:

“A Grateful Dead concert is life.”

In full philosophical flight, Robertson sets out “to explain why otherwise sane people need to hear every note of every Grateful Dead concert.” His observations are, as always, probing and provocative: the music of the Grateful Dead is “emancipating music, the answer to eternity’s enormous Why?” Their recordings provide “Google Maps for the metaphysically inclined life traveller.” Of the 10/18/72 concert he writes that “previously unutilized crevices in your cranium burst with novel connections and questions and insights.” Of a 7/16/76 version of The Wheel: “In a better world, this would be in every religion’s hymn book, the existential mystery of human doing and being all wrapped up in a tidy little package of sighing enchantment.” The Atlanta 5/19/77 concert sums it up: “What we want from our art - what we need - isn’t perfection; what we want is evidence of life - actual life. Of something never not changing and constantly evolving and always capable of surprising and even, occasionally, astounding.” Dan Savoie, in a 519 Magazine review, probably said it best:

“If life were a Grateful Dead concert, Chatham author Ray Robertson would be its philosopher archivist.” (Dan Savoie)

Now it should also be noted that All The Years Combine is not mere hagiography, not just a worshipful idolization of the Grateful Dead. Robertson has plenty of Dead warts and “wasteful wankery” to expose. At times, their music is “static and formulaic … a sloppy muddle … skronky screeching and affectless noodling … over-the-top caterwauling.” An early concert (2/11/69) finds them sounding like a “seriously dosed barbershop quartet” while Bertha (2/18/71) is an “embryonic mess.” Their 10/16/74 concert includes “an hour of improvisational insanity,” while Loser (10/29/77) is “simply unlistenable.” An Iowa show (2/5/78) includes “equal parts too-predictable song selection, unsteady rhythms, and perfunctory performances,” their 12/31/78 version of I Need a Miracle is simply “dumb and derivative,” and a 9/16/78 concert in Egypt finds Garcia “stumbling around in a thick pharmaceutical fog.”

In the same critical vein, while Robertson has nothing against the idea of a band having two drummers (citing the Allman Brothers as an example), he does not hesitate to castigate “when it doesn’t work,” noting their “maddening inability to pick a tempo and stick to it” or their “oompahpah tendency to bash out the beat.” Sometimes the drummers are “an undisciplined mess, the sound of two popcorn machines competing;” at other times “too many songs were performed too boom boom boom flat and fast and rushed, like a gigantic, sped-up metronome.” And those long and tedious drum solos: fuhgeddaboudit! All of this underscoring the band’s "evolving crash-bam-slam style, [sometimes] sounding like just about any bar band anywhere cranking it up to eleven.” By the end, their music had become “predominantly pedestrian.”

So much for hagiography!

There’s no question that Robertson has put in his ten thousand hours of listening to a band that recorded almost 2,350 concerts over their thirty year career. And I mean really listening, as in “Check out the beautifully beguiling chords he conjures up at around the ten-and-a-half minute mark of …”

In All The Years Combine Robertson demonstrates an encyclopedic knowledge of every aspect and nuance of their recording career, both live and in the studio. It’s no surprise he was invited to contribute liner notes to a pair of the band’s archival releases. I suspect that over time All The Years Combine may well become the go-to reference regarding the Grateful Dead’s recording history.

(If anything, there’s too much detail. Do we really need to know that 5/2/70 “is the fourth-to-last performance of Viola Lee Blues,” or that 6/10/73 included the “fourth-to-last Box of Rain to be played for thirteen years,” or that on 11/14/71 “the group would wisely drop [a Hank Williams cover] after twenty-one performances,” or that Stella Blue of 7/18/76 was “not as magnificent as the versions from 11/4/77 or 10/20/78,” or that the Dead incongruously covered Marty Robbins’ El Paso “a staggering 389 times.”)

Petty quibbles aside, I found All The Years Combine to be a fact-filled, fun-filled, exuberant, and gratifying experience, not just for the inside scoop on this durable and ever-changing band, but also for the sheer joy of Robertson’s mastery of story-telling and succinct characterization (he once described the septuagenarian Rolling Stones as a “stageful of old men pathetically parodying their youthful selves”).

With his legendary lexical dexterity, Robertson informs us that by the late ‘80s the Grateful Dead had “outlived glam and disco and punk and New Wave and No Wave and every other kind of wave.” And in the final descending trajectory of their three-decade story arc (even as they reached a never-dreamed-of “gargantuan scale of success”) the band was often “stuck in quicksand and trying to jam its way out of the sonic sludge,” while their faithful tribe of tie-dyed Dead Heads had been replaced with “rabble-rousing fans who were ready to get down and par-tay [with] fist-pumping obliviousness.” Here, in seventy-five perfectly chosen words, Robertson captures the sad denouement of those final years:

“Everywhere they played, it seemed, fans without tickets were tearing down fences and facing off with cops and turning every show into a dance with destruction and a drug bust waiting to happen. In the end, too many counterfeit Dead Heads (Dead Heads don’t crash fences) fatally upset the fragile Grateful Dead ecosystem, crowding Dead shows with thousands of yahoos in backwards baseball hats who didn’t know the difference between getting high and getting wasted.”

At the end of the Beatles’ glorious decade, John Lennon famously sang: “the dream is over.” By the Grateful Dead’s final concert (7/9/95) at Chicago’s Soldier Field, in front of 100,000 people, the band members onstage may well have wondered whether, in “their overeager attempt to keep the dream alive,” they had stayed too long. Three weeks later Jerry Garcia was dead from a heart attack, and the “dream they dreamed one afternoon long, long ago” was over.

One of the unexpected pleasures of this book is the fun of easily finding and listening to whatever concert or song is under discussion. While it must have taken Robertson a great deal of time and money to amass his personal collection of Grateful Dead concert tapes (he calls himself a “Headphone Head”), I can simply type the concert date and song into Google and voilà, I’m hearing what Ray is describing. This was particularly enjoyable for me (being a life-long amateur blues guitarist) whenever Garcia’s blues chops were noted: on a very early It Hurts Me Too (10/22/67) I can actually hear Garcia “sounding like a very talented beginner figuring out the blues.” Similarly, I hear him “lost temporarily in some sub-Clapton blues wankery” on 11/14/71, or “at his Clarence White-ish string-bending best” on 11/15/71, or delivering his “best-ever blues shot” on 12/19/73. What a joy to listen along to what Robertson is so perfectly describing.

There is a 15-page “Hidden Track” at the end of All The Years Combine, where Ray Robertson reminisces about his long strange journey from a 14-year old in Chatham Ontario (winning a Grateful Dead-framed mini-mirror at the county fair) to writing this deeply researched and deeply rewarding account of the Grateful Dead’s own long strange journey. “Music has always been at the foundation of everything I’ve written,” he says, and Ray Robertson aficionados may well recall the country-and-western dilemma of James Thompson in Home Movies, or the twelve musical profiles constituting Lives of The Poets (With Guitars), or the Gram Parsons-like musical iconoclast at the centre of Moody Food, or the Dead Head narrator of Estates Large and Small. Considering the “sundry joys delivered and the aural epiphanies provided,” it was inevitable that Robertson would, as he says, “eventually get around to” this thorough and comprehensive portrayal of the “cracked cosmic charm … propulsive pluck … and charming backwoods yarn” that is the Grateful Dead.

But it’s more than the just the music of the Grateful Dead that underlies Robertson’s identification with this band; it’s also their don’t-give-a-shit aesthetic. Considering that the band members grew up in California’s drug-laced ‘60s (and often performed at Ken Kesey’s legendary Acid Tests) it’s no surprise that they would acquire an LSD-tinged perspective of a universe unfolding at its own pace, where there’s no sense getting uptight about anything. And I believe Ray Robertson shares the Grateful Dead’s go with the flow, let it be attitude. When I criticized the band’s endless and tedious on-stage tuning marathons, Ray replied that “I actually think their on-stage tuning is swell, indicative as it is for not giving a shit about ‘show biz’ values.”

I once attended one of Ray’s book launches in a book/games store. While he read his latest bon mots to about thirty assembled supporters, the “games” side of the place was a cacophony of CRASH! BOOM! BANG! BOING! Annoyed by the inconsiderate racket, I had the urge to confront the gaming children (and their parents) with a polite “We’re reading here. So SHUT THE FUCK UP!” Ray, however, in classic Grateful Dead I-don’t-give-a-shit style, didn’t miss a beat, and just kept on reading. So I think it’s much more than the Grateful Dead’s music that he’s celebrating in this book, it’s their attitude: no matter what life throws at you, keep playing, keep pumping out the joy, keep making art.

“My name is Ray,” he says unapologetically at the end of the book, “and I’m a Dead Head.”

Myself, I’m still not a Dead Head. Although, having listened to many of the selected concerts in conjunction with reading this exuberant and fascinating tale, I must admit that I can now appreciate (okay, enjoy) the Grateful Dead a lot more than before. But most important of all, after reading All The Years Combine: The Grateful Dead in Fifty Shows, I appreciate and enjoy more than ever the story-telling mastery, the linguistic fireworks, the lexical aplomb, and the ribald wit of Ray Robertson, Canada’s Jerry Garcia of the literary keyboard.

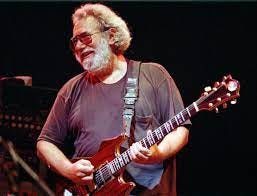

Hello! Fun read. Just the tiniest correction: the photo isn't from 7/9/95. Fare Thee Well (which it's from) was 20 years later...

Very nice and well put, celebrating Ray's style while keeping your opinions of The Dead real. You did the work while I just enjoyed the ride reading and listening. You're both obsessive with your approach to writing and it shows well. I like the way you provide so many examples of Ray's literary gift, the types of characters he creates, his view of what's important and the rhythm of his words.